having too many online friends can mean others perceive you as

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research CenterArticle Contents Too good? The relationship between the number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook CiteStephanie Tom Tong, Brandon Van Der Heide, Lindsey Langwell, Joseph B. Walther, Too much business? The relationship between the number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook, Computer Mediated Communication Magazine, Volume 13, Number 3, April 1, 2008, Pages 531-549, Summary A central feature of the online social media system, Facebook, is the connection and links between friends. The sum of the number of friends of one is a feature shown in the profiles of users as a trace of the connections of friends that a user has accumulated. In contrast to offline social networks, individuals in online network systems often accumulate friends who number several hundred. The uncertain meaning of the condition of friend in these systems raises questions about whether sociometric popularity transmits attractive in non-traditional and non-linear forms. One experiment examined the relationship between the number of friends that a Facebook profile presented and the qualifications of observers of appeal and extraversion. A curvilinear effect of sociometric popularity and social attractiveness emerged, as did a quartic relationship between friend counts and perceived extraversion. These results suggest that an overabundance of friends' connections raises doubts about the popularity and convenience of Facebook users. New forms of computer-mediated communication (CMC) are asking questions about the relationship between communication activities and interpersonal trials. The communication technology has evolved beyond the means by which the senders had more or less complete control over the print-related information that the recipients could observe. With the advent of new social technologies, users no longer have to rely on an individual's self-composed emails, chat statements or personal web pages to get impressions on a subject. Users use unique strategies for CMC including archived transcripts of discussions and chats, browse personal and institutional websites, or use search engines to discover a variety of information repositories (e.g., "googling") (). Google's searches will also soon lead to entries on certain social media sites such as Facebook, another new source of social information. Social media sites such as Friendster, MySpace and Facebook have become immensely popular. The rapid adoption of these systems raises questions about the functionalities they offer that make them so popular, and about the communication dynamics that are shaped by their use. The dissemination of social networks can be seen in various usage statistics: MySpace attracted more than 114 million visitors worldwide in July 2007 (). LinkedIn, which allows users to connect with each other for professional and social purposes, has recently reached the "brand of 10 million members" with 130,000 new members joining each week (). The aim of this study is the Facebook social media site, which was originally created as a site for university students, but now includes anyone with an email address you want to join. With an estimated 18 million members in this writing, Facebook is now the sixth most trafficked website in the United States () and the top website in Canada, as a million new users establish accounts every week (). More than 52 million people worldwide have visited the site (). Users can create profiles that describe various attributes about themselves as their hometown, birthdays, preferred activities, etc. They can expand their social networks by asking for someone else's friendship. These friends communicate within Facebook mainly by posting statements to each "walls" profile. Being designated as "friend", an individual directs the Facebook system to initiate an application to be recognized as a friend of someone, to whom both parties — the friend asks initiator and the friend requests the sender — must agree. When individuals become friends, the system reveals their personal profiles, as well as all their links with other members of their social networks. New connections of friendship often snowball through the networks of friends enlarging and superimposing it started. Given these types of links that provide Facebook and similar systems, the sites are more interesting for communication researchers because they are specifically dedicated to forming and managing impressions, relational maintenance and relationship search. They are novel because, compared to the typical conversations and in contrast to the traditional CMC, the information on these sites contains information provided not only by the creator, but by the friends of the creator, not to mention by computer programs integrated in the systems themselves. Another important reason to examine these systems is that they reveal how people manage their social networks, both in a way and in size. Much of the value of these sites is derived from its manifestly visible social network of friends of users, or at least known, who also have accounts in the system. While research on traditional social networks suggests that the number of people with whom an individual maintains close relationships is about 10-20 () and the total number of social relationships that people manage can be about 150 (; ), studies that examine social networking sites suggest affiliations that often dramatically exceed this figure. A recent study found that a sample of Facebook users at a university reported an average of 246 friends (), while another reported a similar finding of 272 friends (). The impact on the judgments of observers of the presumed size of the social network itself, as demonstrated by this study, challenges the conclusions drawn from traditional research. An additional issue raised by social media sites is the meaning of "friends" in these environments. Some observers speculate that the meaning of a friend is wider than conventional understandings. In spite of this breadth, there may be a higher limit to the extent that people can promptly support even superficial relations, and statements above that limit, as discussed in this study, go back to the success of the management of impressions. This particular study tried to take these issues into account by focusing on the effect of a feature of the Facebook system: the number of friends a user intends to have the Facebook system. This feature allows researchers not only to examine the power of a signal in the Facebook system, but also to explore previously invisible relationships between traditional attributes—population and attractive—which are facilitated by technology in non-traditional ways. Online Printing Formation and Social Networking SitesAuto, Friend and System as Source Previous studies on online print formation have shown that individuals can and make impressions of others through various places of CMC (see for review). The theory of social information processing (SIP); ) suggests that people use any information available within a CMC environment with which to form impressions, despite the absence of non-verbal cues that normally drive impressions in offline communication. Although the IAPA theory has focused on a variety of types of information in the past, e.g., language and content style, chromenic (see revision ), and photographic or biographical information (), new data as network-sized coefficients are not beyond the scope of the logic of theory. At the same time, the theory has not considered incidental information, i.e. information that was not instigated through the volitional behavior of communicators, transported with some level of intent. The information generated by the system is not within the class of variables that the IAPA has originally foreseen. There are numerous volitional councils on social networks. Facebook provides means for a user to post information about the self. A photograph, almost always showing the self, occupies a dominant space in the profile. The system also provides categories for user's textual self-describing. Another source of information about your profile comes from other members of the social network: An individual's friends can leave messages on their profile. Finally, the computer system itself leaves information about one's profile, specifying the number of friends with which an individual has willing to have this status. How do these various sources of information affect impressions? The formation of impressions of self-selected statements in CMC is well understood from a perspective of IAPA theory. As for the messages of friends, recent research has shown that messages from the friends wall also affect the judgments of profile owners. It used the Brunswikian Lens (Brunswik, 1956) model in its research by examining the effects of the context on Facebook. The Brunswik Lens describes how observers associate non-behavioral tracks that reside in an environment that belongs to a social actor to infer the personality of that actor. These devices, or "behavioral residues", can be intentionally created or involuntarily, can originate with the target or with others, and can be shown in physical or virtual space (e.g., ). In any case, observers attribute characteristics to objectives based on the things they observe in the space of the target. found that the statements made by the friends of the profile owner had a significant impact on the qualifications of the social appeal observers and the credibility of the profile owner. Wall messages that refer to sociable behaviors by the target increased the favorable ratings of the goals, while messages suggesting excess drink and philandering caused a setback. In addition, the physical attractiveness of the profile owner's friends (as seen on the profile wall) directly affects the profile's physical attractiveness observers' ratings. As such, the observers used behavioral residues generated by the friends of the profile owner (instead of explicit identity claims left by the profile owner) in impression formation processes. While the previous research has examined auto-generated information and recent research examined by friends, the research has just begun to examine the information sent by the machines, in the form of the coefficient that reflects the size of the social network of one. We suspect that the sociometric information found on Facebook also conveys impressions. The fact that one of the fundamental functions of social networking sites such as Facebook is to make visible and navigable the nature of one's social network suggests that this information can serve not only to establish how well alike an individual is, but also to provide clues about the social status of the profile owner, the physical attractiveness or credibility. In other words, a network-sized coefficient should constitute behavioral waste. It should reflect observers how an individual relates to others as to how many people get in touch, as an indicator of popularity. The network size coefficient also reflects how individuals use the Facebook system, that is, the extent to which they use it normatively or relatively excessively, and consistent with the Brunswik Lens approach (Brunswik, 1956), these perceptions can lead to judgments about other features that the profile owner probably possesses. To understand what meanings these coefficients could be awakened in observers, we review the research on the background and consequences of sociometric popularity, which suggests positive linear effects of friends we have social assessments. Then we examined the recent conjectures about the technological transformations of the size of the network and the specification of friends, which suggested alternative relationships between friends' counts and social assessments. Effects of popularity, offline and research of online popularity An approach to understanding the effect that the visible friend can have on the assessments comes from the assumption that the number of friends in has is a popularity index. Traditional research that investigates offline popularity divides the notion into two buildings: popularity and sociometric popularity perceived by pairs (or perceptual). Perceptive popularity refers to judgments about individuals who are members of a group or class who are believed to be valued by their members. For example, children and adolescents described as popular perceptually were more socially dominant in social interactions; however, these individuals were not necessarily well-liked by the evaluators (). Several studies have shown that those people who are perceptually popular are also more likely to be qualified as self-confidence, stuck, more likely to start fights, and less likely to be subject to social mockery or ridicule (). Of greater interest for current research is the construction of sociometric popularity, which corresponds to the number of friends or connections that one has, which can be reflected in the coefficient of friends shown in the profiles of Facebook users. Sociometric popularity is also associated with a series of social assessments. Sociometrically popular individuals receive more positive ratings on measures of like and potential friends from peers. In addition, popular sociometric individuals are judged as more reliable and friendly than perceptually popular counterparts (). A meta-analysis carried out by revealed that sociometric popularity is associated with physical attractiveness: the most physically attractive is the most popular sociometric. This association takes place between children and adults. For example, he studied the influence of physical attractiveness in the preferences of kindergarten students of potential friends. When two pictures of children of the same sex (one previously qualified as attractive, the other non-attractive), kindergarten students chose the attractive child to be their potential friend more often than the unattractive child. The previous research suggests that people simply prefer to associate with those they find physically attractive. Thus, if people prefer to socialize with attractive people, then those who are more popular should also be seen as more physically attractive. Other trials are also associated with attractiveness, which may also have some relation to sociometric popularity. Attractive individuals are qualified as more intellectually competent than non-attractive, among adults in the workplace () and children in schools (; ). meta-analysis revealed that although the differences in evaluation were stronger for children than adults, when compared "with other effect sizes in the social sciences", the sizes of the effects obtained were still "incommonly large" for both groups (p. Attractive individuals are judged more favourably than non-attractive individuals in a variety of different dimensions, such as academic/development competition, interpersonal competition, social attractiveness, extraversion, self-confidence and occupational competition. The well documented "halo effect of attraction" further suggests that attractiveness and social acceptance are linked (; ). The previous research suggests that observers make inferences about the popularity of the target individual that in turn affects their assessments of the physical characteristics and personality of the goal of a variety of ways. Since there seems to be a reciprocal relationship between popularity and attraction (and other assessments), it seems plausible that an individual who seems to be popular on Facebook (i.e., has many friends) is seen as more physically attractive, and also as having more socially desirable personality and fashion features. Popular/attractive research suggests nothing more than a linear association for this relationship. Popularity of Facebook, at a pointThe search supported the idea that the number of friends indicated in the Facebook profile triggers positive social judgments this way. Kleck et al. presented participants with Facebook profile models that varied in the number of profiling friends seemed to have: 15, 82, or 261 friends. (In addition, Kleck et al. varied the nature of the pictorial chart in the profile so that the profile contained text information about the owner of the profile only, text information and a static photograph, and text information with the addition of a video from the owner of the profile, although pictorial variations had no effect on any of the result judgments.) The number of friends affected the trials. Analyses revealed that the observers distinguished between the bass (15 and 82 friends) against the high (261 friends) conditions of friends in several qualifications: Popularity, kindness, heterosexual appeal and the trust of the profile owner were greater when there were a high number of friends in the profile of an individual who when the lower coefficients were shown. The exploratory study of Kleck et al. answered some questions while raising others. It helped establish that Facebook coefficient friends — a subtle sign among many — triggered social assessments in a pattern consistent with past popularity research. The topic could be resolved except when it is considered the rank of the number of friends that have been observed in other Facebook studies. For example, a recent survey found that students reported an average of 272 Facebook friends (). Another study found that the average Facebook friends reported by a sample of university students was 246, with a standard deviation of 184 (). These findings raise the elementary question if the positive relationship determined by persists in the larger ranges of friends who have empirically observed themselves in other populations. Beyond elemental skepticism, however, there are reasons to predict that the presence of an even greater number of friends in a Facebook profile leads to different social judgments than the dynamics of popularity, alone, would suggest. Other publications have speculated that the meaning of friends changes in social networks, especially as numbers increase. In Brunswikian terms, the highest sociometric counts can be interpreted as behavioral residue of something other than genuine popularity. Theoretically, the effect aroused by Facebook's coefficient of friends, documented by Kleck et al., may not extend beyond certain limits that imply even greater numbers of friends online. Change of Friendly Meanings in Social Network Systems On Facebook, the meaning of friend does not always have traditional connotations, and therefore the sociometric coefficient of the number of friends that one has provides clues of a different nature on the character of one. That is, in Brunswikian terms, the size of the network of one is the behavioral residue of the way the online associations accumulate. Other emerging research suggests that there is a decline in yields in terms of Facebook's policy use with respect to recruitment partnerships. What does it mean to be a "friend" on Facebook? It can mean several things. First, it often reflects that individuals have some form of knowledge that is based on offline interactions. Social media systems can facilitate mixed movement relationships. defines relationships in a mixed way such as those that move from an electronic context to a face to face environment or vice versa. In the case of social media systems we can see many relationships that range between the virtual and the physical quite often. They argue that online social media systems can help people maintain a greater number of close links that people can normally maintain without such technology, as systems allow people to verify the sites of others for updates, reflect new activities, and facilitate brief verbal exchanges through asynchronous wall messages. At the same time, what is labeled "friend" on Facebook often does not correspond to the same offline label, and this difference inflates the potential size of friends' networks. "Friend" has been shown that a large number of people are one of the main Facebook activities (if not) according to Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe (2006). Although Ellison et al. He discovered that a large network of weak social ties through Facebook becomes a source of social capital, another survey reported that approximately 46% of respondents had neutral feelings or felt disconnected from their friends on Facebook (). Ethnographic accounts indicate that among Facebook users it is not rare to request and establish the status of friend among the most hardly known partners (), and it is socially inappropriate to reject a friend request from someone who is familiar (). Therefore, a wide range of types of relationships are represented as friends on Facebook, and each contributes to the total number of friends reflected in the sociometric coefficient, although the designation of friends is "intonized" in which it does not indicate type of relation to the observer (). Therefore, the size of the network of apparent friends in a system such as Facebook can easily become much larger than traditional offline networks, because friendship is in some cases more superficial, because technology facilitates a greater connection to some level, and because social norms inhibit rejections of friends' requests. Despite the flexibility of the association of friends in social media systems, it seems that the judgments about users are based on the coefficients of friends, in ways they documented, but also in other ways. Incredulity and evaluation Social media systems apply social norms to assess whether friendship reaches a point of unbelief or folly. Offline, it seems that there is no limit above the number of friends you can have; the largest social network, the greatest the ratings of the positive attributes (i.e., "Jane has many friends, she must be so nice, kind, reliable, etc."). The gross excesses that Facebook can facilitate seem to violate this relationship. After a point, too many connections can result in negative judgments. A free friendship is observed: , p. 6) note that "on the exhibition on these sites can also be equipped to a popularity contest based on the state of how many friends or friends of friends one has." observed a similar phenomenon with respect to a corresponding social media website, where individuals who freely added superficial friends were known as "many of friends": a pejorative term that was perceived to be perceived. The terms like "Friends' Track" suggest that in this new domain of online social networks, a point comes when too many apparent friendship connections become too much of a good thing. When the number of friends becomes implausible, the apparent sociometric popularity becomes an obstacle, instead of an advantage, to the good impression of the profile owner, according to . In terms of "behavioral residue" Brunswikian, an abnormally high friend can feed the inference that the owner of the profile spends more time superficially loving others beyond a plausible extension, that is, the behaviors he seems to have done are free and disingenuous. This "social overload" seems to be a unique CMC phenomenon that does not generalize out-of-line meetings. Although some individuals may say that they "know everyone" in acquaintances offline, such a phrase is clearly hyperbola. In addition, the literature on offline popularity does not suggest any asyntotic trend in the association of friends counting and positive assessments. Although the line that separates an acceptable from an absurd number of online friends is not yet known, the accounts suggest that the number of individual friends who seem to have on Facebook can awaken a non-linear relationship with the types of social assessments previously associated with popularity. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis: H1: There is a U-inverted relationship in curvilinear between the number of friends that a profile owner has and the perceptions of the profiler (a) social attractive (b) physical attractiveness. H1: There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between the number of friends that a profile owner has and the perceptions of (a) social attractive (b) observers physical attractiveness. Because extraversion is conceptualized as the verb or outgoing is, we do not necessarily expect the curviline relationship with this trait. In fact, it is likely that a profile owner will seem to maintain high levels of online extraversion to accumulate so many sociometric ties. H2: There is a linear relationship between the number of friends a profile owner has and the perceptions of extraversion observers. H2: There is a linear relationship between the number of friends a profile owner has and the perceptions of extraversion observers. MethodologyA sample of 153 undergraduate students at a large university in Midwestern USA voluntarily participated in research in exchange for credit per course. The participants received a URL with which to access a website that showed all the research materials. They were instructed to complete this research individuals using a WWW browser at a location of their choice. This allowed them to see stimuli in a natural environment. The website initially provided information on informed consent. The informed consent material explained that this was a study on the formation of impressions in electronic communication and that they would be asked to make some judgments about another individual on the basis of looking at a sample of some online communication as a Facebook profile, a transcription of an instant Messenger chat, or an e-mail exchange between potential targets. At present, each participant was redirected to a Facebook simulation. After reading the participants the informed consent information selected a link that led to a scheduled javascript routine to randomly redirect the web browser of each participant to one of the five versions of the stimulus (see ). Participants were ordered to view the stimulus material as long as necessary to give an impression to the profile owner. The participants clicked on another link to open and then address the topics of the questionnaire. Standard demographic information (gender, age, university year) and Facebook information (use of Facebook, use of the Internet, number of friends, etc.) were collected and analyzed. After the removal of respondents who indicated that they did not have a Facebook profile and those who reported extreme scores in number of friends, 132 subjects remained on the sample. Analgesics revealed sample sex (53% women), age (M = 20.18, SD = 1.32, mode = 21), and year at school (20% newborns, 28% sophomores, 31% juniors, 19% older, 2% disappeared). Regarding Facebook friends, the analysis showed M = 395.02, SD = 316.03, median = 300, mode = 300. The average was assaulted by some respondents with senior friends; 6 people reported 1000, 1 reported 1200, and 1 reported 2700 friends. Participants reported the number of hours per day spent on Facebook, M = 4.51, SD = 4.31.Stimuli Participants examined one of the five stimuli, each containing a Facebook profile. The elements of these stimuli (e.g. photographs, wall posts, etc.) remained constant over the five versions, except for the number of friends who appeared on the profile as 102, 302, 502, 702, or 902. These intervals were chosen to reflect equal intervals amenable to trend analysis. Specific quantities are suspected to range from the sizes below the standardized Facebook friends networks based on previous research (; ; ) and informal discussions with Facebook users. Other elements of the Facebook simulations were selected on the basis of the results of the previous test with university focus groups. The photograph used to represent the owner of the profile was rated in pre-tests as neutral in the physical appeal, and two positive and negative statements compensated appeared in the "wall" profile (see ). The random selection of male and female photographs used to represent "Friends in Other Networks" remained constant in conditions, and the two photos representing the friends of the wall (i.e., those who made the poles of the wall) were counteracted with one attractive and the other non-attractive. The counter-balancing approach was selected in an effort to promote ecological validity while maintaining a general neutral information fund. All profiles represent women only though the gender effects can be examined in future research. Because most Facebook users rarely have all their friends confined to a network, the total number of friends was divided between three different networks. The primary network shown in stimuli was the university where respondents were enrolled. To select the other two networks, the researchers gave a list of several other universities and colleges in the same state of the USA to an offset group of university graduates comprising the primary network. This procedure generated prestigious qualifications of alternative schools, so that researchers could select two neutral specimens for secondary networks represented in simulation profiles. Most of the friends of the profile owner were represented as members on the primary network with less friends on the other networks. Dependent Measures Data were collected on the physical and social attractiveness of the profile owner using measures created by . The analysis showed an estimate of alpha reliability of Cronbach of .77 for social attractiveness, and α = .80 for physical attractiveness. Post-test articles also included extraversion measures (α = .84) (ResultsHypotheses TestsHypothesis 1 predicted a curvilinear relationship (inverted in U form) between the number of friends that a profile owner has and the perceptions of the profile owner's (a) social and (b) physical attractiveness. To test these relationships, one-way variance analysis (ANOVA) was performed with a number of friends as the independent and attractive social and physical attractive variable as dependent variables. Support was expressed for scenario 1a. The results showed a significant quadratic effect for the relationship of the number of friends in the social attraction, F (1, 129) = 2.78, p = .098, pira2 = .02. To confirm the direction of the curve, the media were subjected to a test of less significant post-hoc differences. The LSD test revealed that the apex of the curvilinear relationship was in the condition of 302. That is, the goals were considered more socially attractive when they had 302 friends. Standard Media & Deviations of Social Attraction, Physical Attraction and Appearing Number of Facebook Friends . Social attraction . Physical Attraction . Extraversion . n 0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0.0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0, . Social attraction . Physical Attraction . Extraversion . n . 102 Friends 4.05 (1.01) 3.50 (0.66) 3.56 (1.08) 24 302 Friends 4.77 (0.87) 3.88 (0.99) 3.48 (0.89) 33 502 Friends 4.38 (1.17) 3.81 (1.24) 4.40 (1.36) 26 702 Friends 4.22 (1.32) 3.73 (1.15) 3.95 (1.06) 30 902 Friends 4.12 (1.14) . Social attraction . Physical Attraction . Extraversion . n 0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0.0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0, . Social attraction . Physical Attraction . Extraversion . n . 102 Friends 4.05 (1.01) 3.50 (0.66) 3.56 (1.08) 24 302 Friends 4.77 (0.87) 3.88 (0.99) 3.48 (0.89) 33 502 Friends 4.38 (1.17) 3.81 (1.24) 4.40 (1.36) 26 702 Friends 4.22 (1.32) 3.73 (1.15) 3.95 (1.06) 30 902 Friends 4.12 (1.14) 3.86 The relationship between the number of friends and the physical attractiveness did not follow the planned curviline relationship. The global F and the specific test for quadratic effects were not significant, F (1, 129) = 2.47, p = 0.119. The 1b hypothesis was not supported. The post-hoc LSD analysis did not show even differences between the five media (see ). Hypothesis 2 predicted a linear relationship between the number of friends a profile owner has and the perceptions of the extraversion observers of the profile owner. A single-way omnibus ANOVA with extraversion as the dependent variable was significant, F (4, 129) = 3.12, p = .02. However, the linear effect specified by H2 was not supported, F (1, 129) = 2.32, p = .13. Rather, a significant quartic effect emerged, F (1, 129) = 5.66, p = .02. The post-hoc analysis by comparisons with LSD showed significant differences in pairs between some of the cells that suggest (a) an invert-U effect in general, with the highest level of extraversion that occurs at the level of 502 friends. Although the perceived extraversion went beyond the apex, the largest number of friends (702 and 902) stimulated not less the extraversion than the apex. However, the lowest number of friends (102 or 302) involved significantly lower extraversion trials compared to the apex of 502 (see full results). It seems that having many more friends actually connotes greater extraversion for Facebook profile owners, something as predicted, but that the association is not a direct linear pattern. The most extroverted powers are relegated to individuals with a greater number of friends. Debate The objective of this research was to determine the nature of the relation between social indicators of the connection represented on Facebook and the social attractiveness, the physical attractiveness and the extraversion of the owner of the profile perceived by others. This study raised questions about the nature of these relationships and subsequently found effects of information generated by the social media system on the perception of others in a social media environment. There is a curviline relationship between the number of friends that profile owners intend to have and the perceptions of others about their social attractiveness. More specifically, on the condition that the profile owner had the fewest friends (102), the individual's social attraction ratings were among the lowest. Evaluations of the individual's social attraction were higher when the profile showed that the profile owner had approximately 300 friends. Beyond that level of friends, the qualifications of the social attractiveness of a profile owner were denied at a level that approaches the condition of 102 friends. Although there were no significant differences between social attractiveness in the lowest and very larger number of friends' conditions, the absolute values of the associated media are trending in the direction that suggests that it is better to have too many friends than to have too few. While H2 predicted a linear relationship, the results gave a complex and quantitative relationship between the number of friends in the owners' profile and perceptions of the extraversion of the profile owner. Although more friends connotated greater extraversion than less friends, the analysis revealed that there were significant deviations of linearity in this relationship, with the highest degree of extraversion associated with a moderately large number of friends, but diminishing in the greater number. It seems that having a large number of friends leads to trials that profile owners are not sociable and outgoing, but are relatively more introverted. The observers apparently infer that an individual with an excessive number of friends has not accumulated them as a result of extraversion, but by some other characteristic. This possibility is consistent with the Brunswik (1956) Lens Approach, which suggests that observers interpret artifacts as clues to the behaviors that one probably committed, of which personality assessment is inferred. Individuals with too many friends may seem to be too focused on Facebook, loving desperation rather than popularity, spending a lot of time on their computers trying to make connections in a computer mediation environment where they feel more comfortable than in face-to-face social interaction (see ). Although these precise interpretations are not revealed in this study, they are consistent with ethnographically based speculations on why "migrating" too many others can lead to negative judgments on the profile owner. Although this interpretation is plausible, the caution is justified to place too much of a premium on the accounts of the participants themselves or observers of the mechanisms by which they conduct trials. Individuals may not be aware of the extent to which friends actually count them. A modest follow-up study explored this issue. In the primary study, the only independent variable active among all Facebook simulations was the representation of the number of friends, and since these coefficients were demonstrablely different (either noted by research participants or not), no manipulation control was justified and no one was performed (see ). However, the question of the knowledge of observers is intriguing and, therefore, a post-hoc experiment was conducted to explore this issue. Students from the same university as the primary experiment (from an intact course), N = 24, were randomly presented one of the same stimuli described in the main study as discussed above, in full sheets, printed in color. These observers were asked to list the impressions on the objectives, and then to list the basis for their trials. Only 5 of the 24 respondents specifically mentioned the number of friends the profile listed. When these identifications occurred, they appeared through the range of friends they have manipulations except for the most normative level (302): 102, 502 (twice), 702, and 902. It appears that while friends' counts had a reliable effect on the initial printing task, the basis of the effect was not something that most observers are consciously aware of. This phenomenon is more consistent with the acclaim effects described by the classical research on human reactions to the exposure to numbers: The short exposure to high or low numbers unconsciously triggers heuristic decision in a variety of environments, leading to partial population estimates, differential bidding and other numerically related irrational effects. However, understanding the precise mechanisms or powers resulting from such anchoring will require additional research. A plausible mechanism that can be explored behaviorally from this study is a possible similarity effect: The optimal number of friends is related to the number of friends of the evaluator. Participants in this study reported a modal number of friends of 300. Since the optimal number of Facebook friends in the stimuli was the closest number to the average number of friends claimed by the respondents, it is plausible that the judgments of social appeal are due to the similarity of the emitter to the target. If this is the case, then if observers who have 100 Facebook can judge an individual with 300 friends to be less like them and therefore less socially attractive than an individual with 100 friends. Also, the evaluator with 1000 friends can find the profile owner with 900 more similar friends and therefore more socially attractive than the profile owner with 300 friends. The similarity effect was examined after-host through a multiple regression analysis in which social attractive scores were returned in a term that represents the interaction of the number of friends in stimuli by the number of friends surveyed (adjusting the friends of the respondents have a log-normal transformation due to the non-normal distribution of that count; ). The analysis was not significant, adj. R2 = .01, F (1, 130) = 2.33, p = .13. It seems that social appeal assessments attributable to the number of friends in a Facebook profile are not a significant function of the observer's friends' count. It seems reasonable that some normative rules, deviations from which derision is triggered in some way, and judgments of greater social appeal go to those people who are closer to the media. Such a process can be considered or heuristically developed. Contrary to predictions, there was no relationship between the number of friends that had a profile owner and the physical appeal attributed to the profile owner by others. It is perhaps not surprising at all that the number of friends did not affect perceptions of physical appeal. First, a photograph of the same owner of the profile was present in each of the experimental stimuli. A small variation of an impression that was strongly and directly tied by a photo would be expected. Although the previous research has found that the physical attractiveness of the owner of a profile is affected by differences in the attractiveness of those who comment on the "wall" of a Facebook profile, as well as what those comments contain (), these factors remained constant in the present study. Therefore, it seems likely that the presence of these other qualifications of physical appeal beyond a level that would be influenced by the number of friends that are intended by the profile of one. It is possible that, in the absence of photographic signals and messages, the number of friends that a person can serve as a more powerful point in the determination of physical attractiveness, in addition to other judgments. The effect sizes in this study were relatively small. This raises concern about whether manipulations were inadequate, whether the experiment captured ecologically valid assessments, or whether the real effect of the number of friends on Facebook is actually small. It should be noted, however, that significant results were achieved despite an infinitely small experimental manipulation. The content of the Facebook profile remained constant with the exception of the alteration of a value of a Facebook profile information element (through the alteration of friends' networks so that the sum of friends totaled the number presented in the profile). Given this small induction and subsequent results, it seems reasonable to conclude that sociometric information such as the number of friends you have is a relatively powerful point in various social trials in a social network environment. Current findings extend and modify from the investigation. Kleck et al. argued that a greater number of Facebook's apparent friends were imposing positive impressions on a profile owner. This study confirms that assertion but only to a certain extent. In the light of this study, Kleck et al.'s manipulation was restricted in rank - only low and medium number of friends were tested- which led to the linear relationship their results suggested. His finding was replicated within the current design, for the difference between 102 and 302 friends. However, current results indicate that people with an excessive number of apparent friends do not continue to increase positive assessments. This study raises questions for online Impression formation and management theories about the nature of the role of sociometric information in online and offline impressions. posited that the warranting value of information (the degree to which information about oneself is more or less self-presented rather than presented by others) raises its value in making judgments about what a person found online is really like offline. First-person messages about oneself on the Internet are of less value to a rater than third-person messages about an objective, according to the supporting principle. It seems reasonable to ask, from this perspective, what is the role of sociometric information in the process of forming impressions. Sociometric coefficients are not clearly first or third-person reports on an individual. Rather, the sociometric data, in the case of representing the number of accepted requests for friendship from social networks, are a behavioral residue of the behavior of a profile owner and the behavior of a particular set of friends. This feature could cause the number of friends to moderate in the supporting value. Alternatively, since requests from friends should be sanctioned by others, they may have a strong supporting value. Moreover, since sociometric information is generated by the mechanics of the social media system itself, rather any specific person, we must expect this information to be considered truthful by the viewers. That said, given the common knowledge that Facebook "friends" are often simply known, and that the rejections of friends' requests are uncommon (), the veracity of the apparent tendency to gather friends without meaning online (or the apparent inability to gather "sufficient" friends) is likely to lead credence in the virtual environment. Future research should assess the weight of this information in the context of people who meet outside the line or in Internet discussion spaces "Facebooking" to each other as a means of reducing the uncertainty of initial knowledge. In conclusion, this study advances in the important finding that sociometric data such as the number of friends you have on Facebook can be a significant sign by which individuals make social judgments about others on an online social network. This study helps to note that in the case of social attraction and extraversion, people who have too many friends or too many friends are perceived more negatively than those who have an optimal number of friends. As for sociometric information, future research should examine whether the most detailed sociometric data (i.e., the state of friend, connection, etc.) have some effect on the profile owner's assessments in different types of populations and configurations. More broadly, future research should investigate how individuals use other types of machine data (generated by the website) when doing social judgments from others. It would be of interest, as well as academic and practical value, to apply these issues to aspects of other social networking sites. While MySpace, Orkut and Linked In all are rooted the same phenomenon of social networks, there are some characteristics and attributes of each one that are unique. For example, in MySpace, an individual may be a friend of a professional musical group or other collectives, and in such cases it is not likely that he has had any face-to-face contact with the friendly entity. Does it mean somewhat similar sociometry in such an environment, where the friend's label persists but its meaning is even darker? Do affiliations point to something more than full popularity or despair, or do some meanings cross contexts? What is the range of trials that result from several signs of affiliation, as new communication technologies change the definitions of terms of relationship and modify the demonstration of social networks, if not the nature of our social networks? As researchers advance in understanding how people interact with each other in online social media environments, these are some of the questions that will further inform our understanding of these new communication technologies. NotesReanalysis restricted only to those participants with less than 1000 friends surrendered M = 340.66, SD = 192.55, a figure still far above those reported in other studies mentioned above. It may be that, compared to previous studies, Facebook has gained more users and users have discovered greater connections. A rule of statistical significance of p ReferencesAbout the authorsStephanie Tom Tong (B.A., University of California, Davis) is a graduate student at the Department of Communication at Michigan State University. Their research interests include how communication technology impacts training, development and termination of interpersonal relationships. Address:459 Comm Arts & Sci Bldg, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48824, USABrandon Van Der Heide (M.A., Michigan State University) is a PhD student at the Department of Communication at Michigan State University. Its main interest is in the field of communication technology. Specifically, he is interested in social influence, small group processes and the formation of impressions in a variety of online environments. Address:553 Comm Arts & Sci Bldg., Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48824, USALindsey Langwell completed her BA in communication at Michigan State University in 2007 and is currently a digital network assistant for Universal McCann in New York where she continues to explore interests in social media and emerging media systems. Address:622 3rd Ave., New York, NY 10017 USAJoseph B. Walther (Ph.D., University of Arizona) is a professor at the Department of Telecommunications, Information and Media Studies, and the Department of Communication at Michigan State University. His research focuses on the interpersonal dynamics of communication through computers, personal relationships, working groups and educational environments. Address:565 Comm Arts & Sci Bldg., Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48824, USA Email Alert s Related Articles inCiting Articles via ConnectResources ExploreOxford University Press is a department at Oxford University. In addition, the University's goal of excellence in research, scholarship and education by publishing around the world or This PDF is available for Subscribers OnlyFor full access to this pdf, enter an existing account or purchase an annual subscription.

How Social Media Is Taking Away from Your Friendships

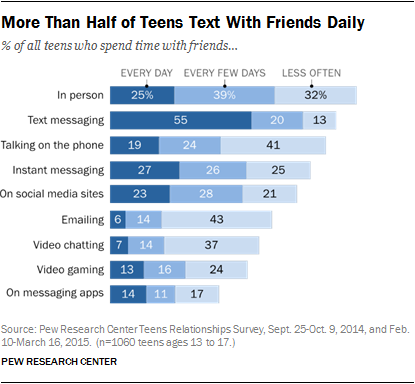

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

/2795906-what-is-the-halo-effect-5ae866adc673350036f1657f.png)

Why the Halo Effect Affects How We Perceive Others

/media/img/mt/2020/04/Webart_BestfriendsCorona_01/original.png)

When Your Friend Ignores Social Distancing - The Atlantic

Toxic Friendship: 24 Signs, Effects, and Tips

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

Should You Reach Out to a Former Friend Right Now? - The New York Times

Teens, Technology and Friendships | Pew Research Center

One-Sided Friendship: 14 Signs, Effects, and Tips for Ending It

How Can I Ask My Friends to Wear Masks? Talking to Friends, Family, Kids, and Coworkers About COVID-19 Safety - COVID-19 - Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Toxic Friendship: 24 Signs, Effects, and Tips

Why Talking About Our Problems Helps So Much (and How to Do It) - The New York Times

How Discord (somewhat accidentally) invented the future of the internet - Protocol — The people, power and politics of tech

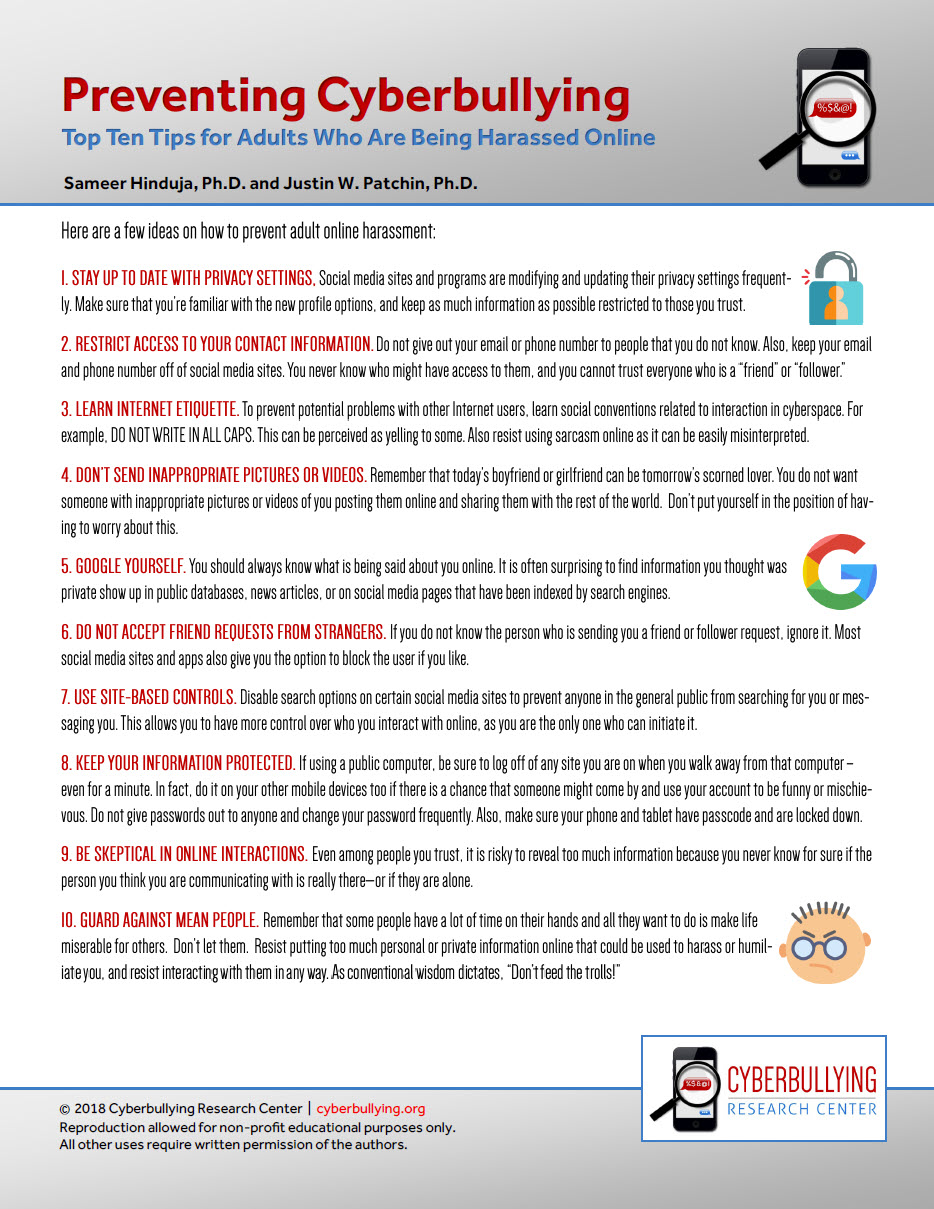

Preventing Cyberbullying - Top Ten Tips for Adults Who Are Being Harassed Online

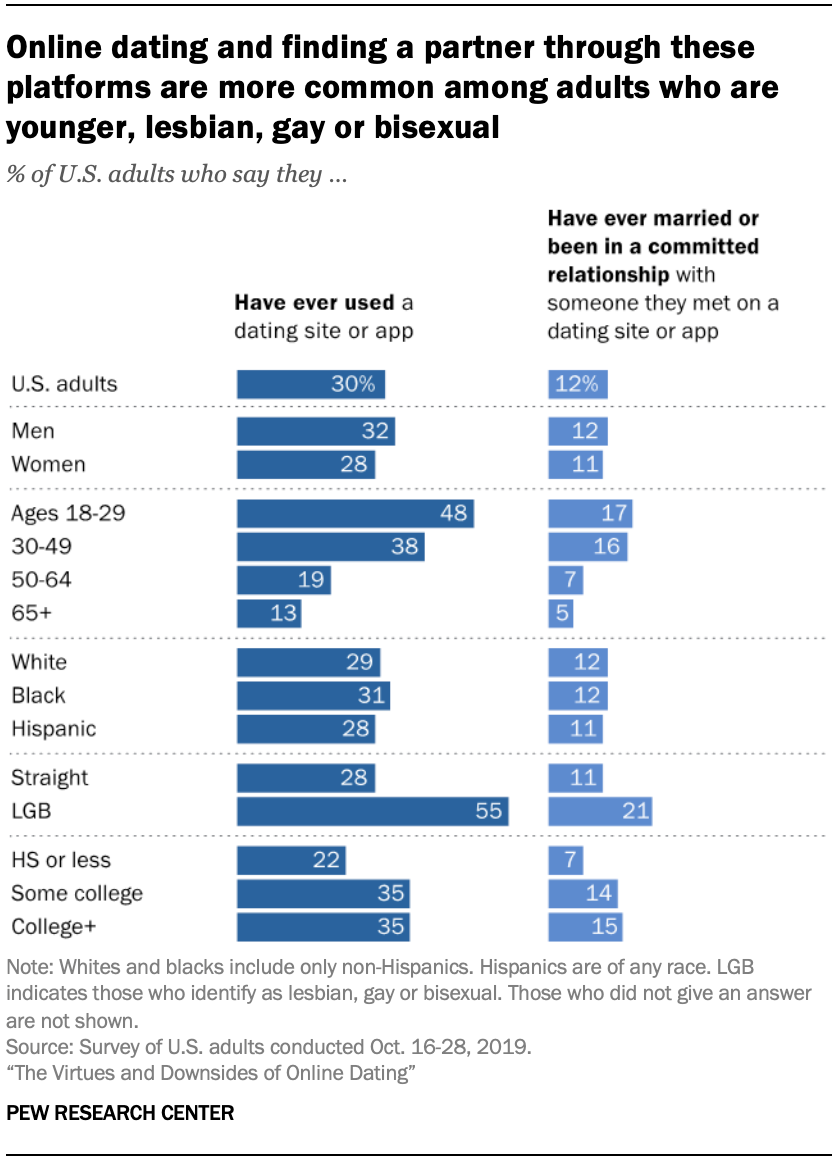

10 facts about Americans and online dating | Pew Research Center

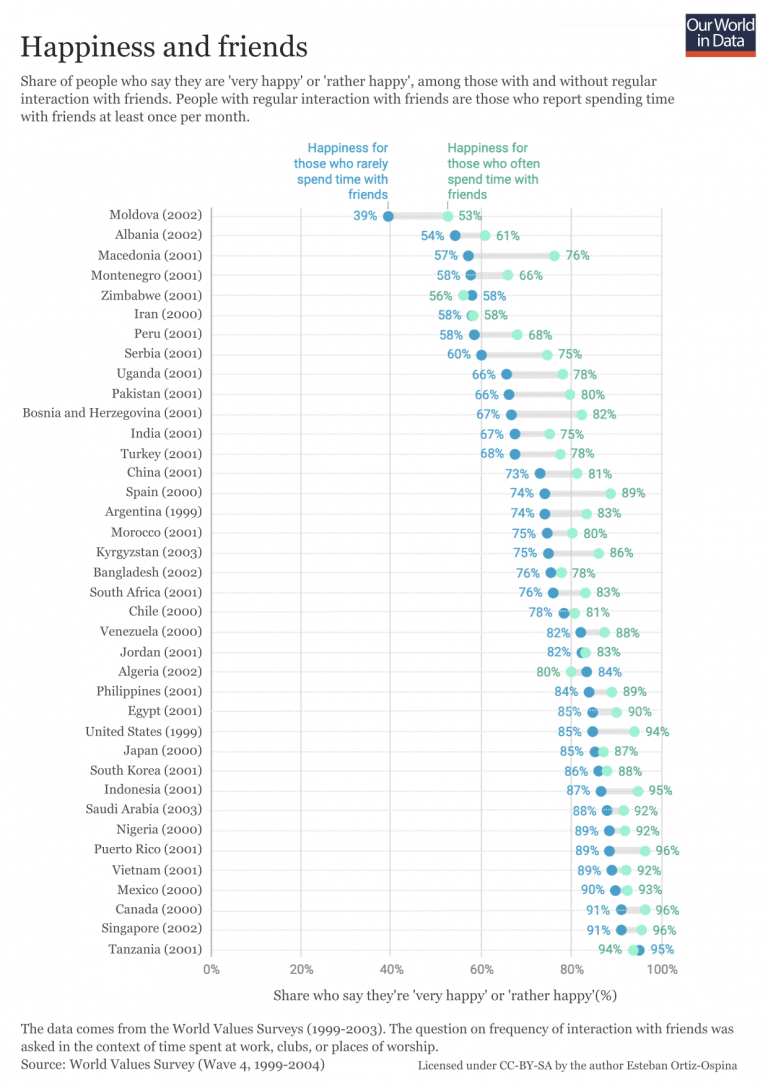

Are we happier when we spend more time with others? - Our World in Data

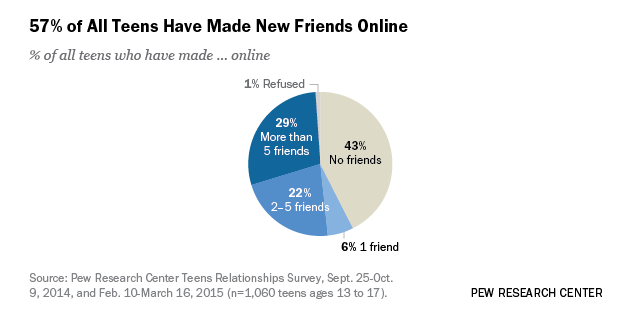

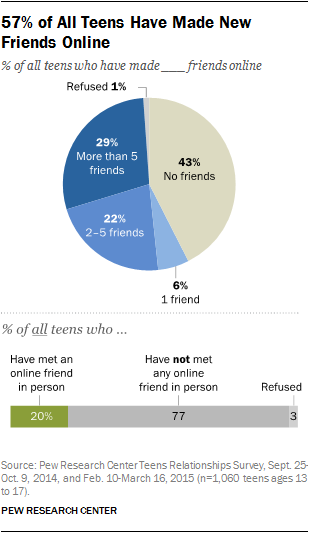

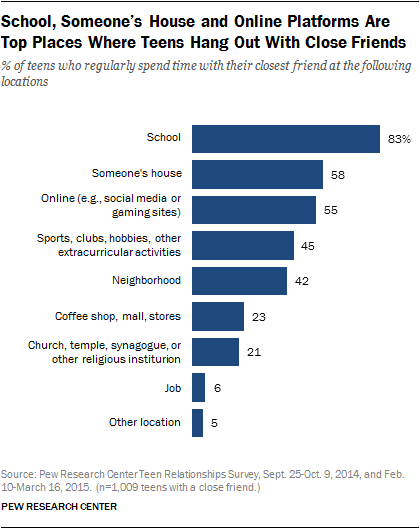

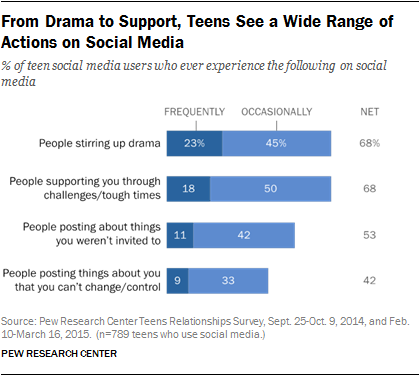

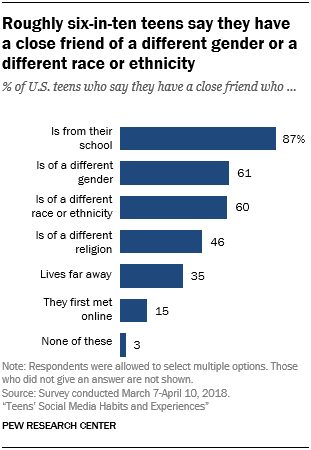

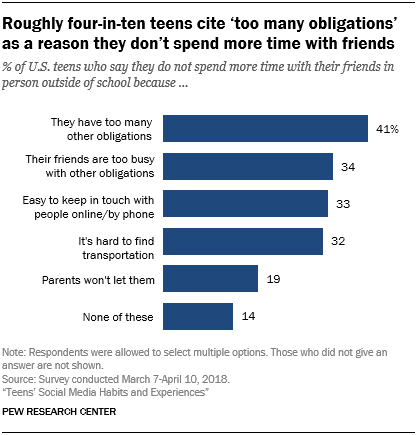

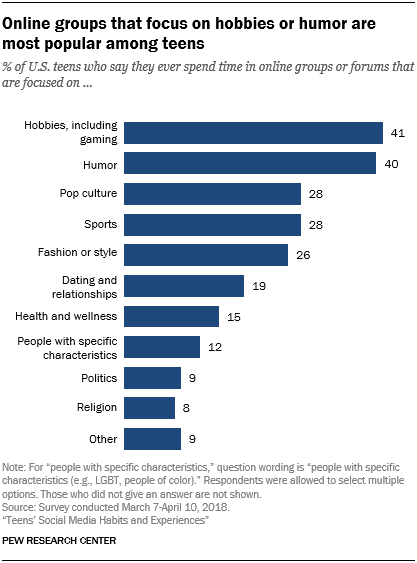

2. Teens, friendships and online groups | Pew Research Center

How to Be a Better Friend - Smarter Living Guides - The New York Times

How to Make Friends Online (+ Best Apps to Use)

10 Words That Describe Toxic Friendships

I never expected to lose so many friends after becoming a parent

/what-is-rejection-sensitivity-4682652_V2-7c551da9d81d4673a1ae28d07906f44a.png)

What Is Rejection Sensitivity?

4 Ways You Can Shape How Others Perceive You and Build an Outstanding Personal Brand | LinkedIn Talent Blog

How to Get Over That Friendship Insecurity as an Adult | The Everygirl

How Social Media Is Taking Away from Your Friendships

Why Coincidences Happen and What They Mean - The Atlantic

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66763703/WeirdTime_v3.0.jpg)

Why quarantine has made time feel so weird, explained - Vox

Leading Blog: A Leadership Blog

How to Have Closer Friendships (and Why You Need Them) - The New York Times

2. Teens, friendships and online groups | Pew Research Center

/what-is-self-esteem-2795868_FINAL-1d12e4b54f20465ab8dfd7350b614fee.png)

What Is Self-Esteem?

What Happens in Our Brain When We Dislike Somebody - Headspace

2. Teens, friendships and online groups | Pew Research Center

/media/img/posts/2016/02/Screen_Shot_2016_01_28_at_11.44.25_AM/original.png)

Why Coincidences Happen and What They Mean - The Atlantic

When People See the Worst in You: Perceptions Aren't Always Accurate

Problems with Online Communication: Things You Should Remember | Success by LiveChat

Posting Komentar untuk "having too many online friends can mean others perceive you as"